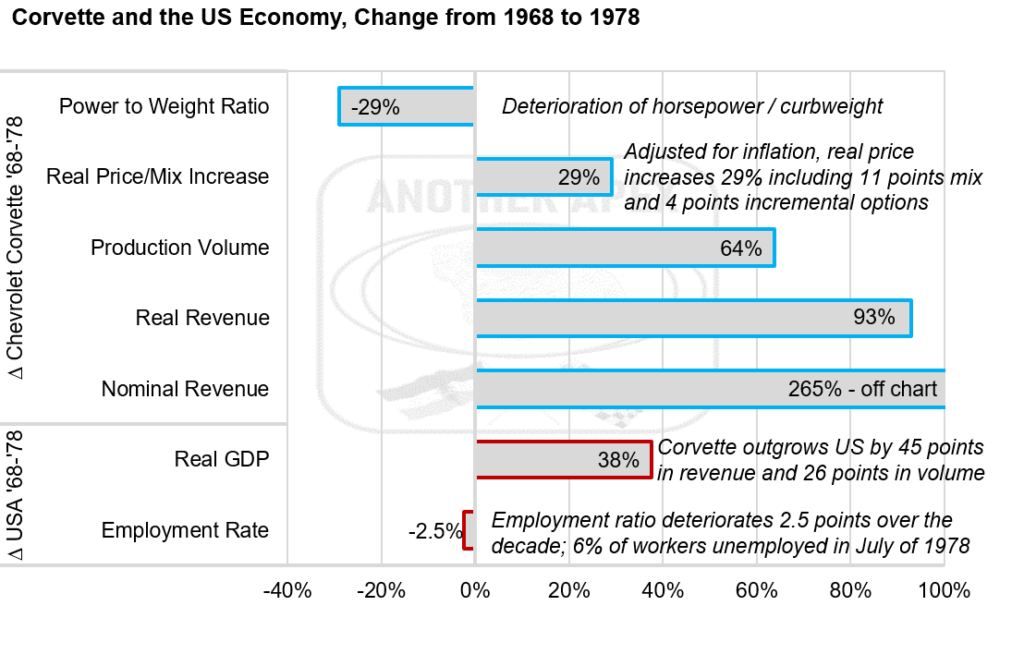

For a moment imagine a decade old body with fifteen year old bones that had lost a third of its quickness. Further, imagine doubling the price of this seemingly obsolete vehicle over a decade; 75% to keep up with rampant inflation and another 25% for good measure. Would sales of such a tired seemingly overpriced car be a runaway success?

Note: Nominal MSRP increased 116% from 1968 to 1978, 27% from real pricing and 89% from inflation (CPI). GDP and CPI comparable to model-years (ending of 2Q figures captured), change in revenue assumes GM receives 75% of MSRP and dealers absorb any variance from MSRP.

Source: Corvette Museum Archives, GM, Federal Reserve, The Complete Book of Corvette, Original Corvette The Restorer’s Guides 1963-1967 & 1968-1982, Tom Falconer, Motorbooks 2001 –and- 2008, Mike Mueller, Motorbooks 2006, and Another Apex estimates 8/28/2019

In the back of my head I can hear murmurs of a microeconomics Professor saying something about price elasticity. But unfortunately these recollections are mostly like the teacher’s trombone voice in Charlie Brown cartoons. But no projections are needed.

Relative to the third generation Corvette’s debut in 1968, production volume increased 64% and revenue almost doubled in 1978. Yet vehicle performance had crashed; straight-line acceleration was an almost futile pursuit due to regulation. Did Americans not really buy Corvettes for speed after all?

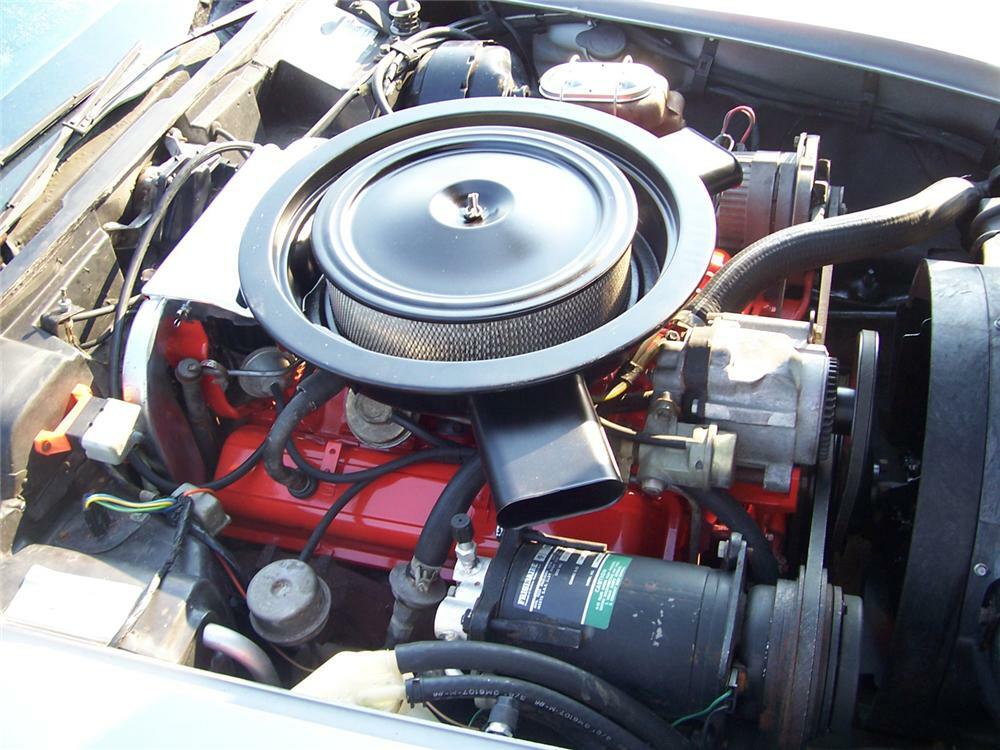

To put the lack of performance into perspective, it would take only six of the ’68 base model’s eight cylinders [4.0 of its 5.4 liters] to match the output of all eight cylinders of the base ’77 Corvette’s engine [5.7 liters].[1] Yet the weaker ‘77 Vette – with hundreds of extra pounds in catalytic converters, mufflers, and bumpers – was so popular that the C3 earned a refresh the next year and remained in dealers well into the 80s.

With the solid-lifter LT1 gone and the big-block’s days numbered, from ’73 to ’80 muscle oriented buyers still had the option to upgrade to the 15-20% higher output L82. But only about a fifth of these Corvettes tacked the extra 5-6% onto MSRP to throttle the more potent small-block. Instead, the vast majority of buyers increasingly preferred dramatic new sound systems often finished with 8-track players, rear speakers, and power antennae. In fact, 15% of ’78 buyers – apparently fans of Burt Reynold’s ‘77 box-office smash Smokey and the Bandit – had the factory install a new CB radio option for another 7% of MSRP. You can’t outrun the radio L82 buyers!

Indeed as a percentage of MSRP, late C3s were generally more “loaded” than early C3s. This contributed to a fantastic 14-29% increase in real price (calculation varies due to mix) as the C3 started its second decade in 1978.[2] Where all these – new and apparently wealthy – Corvette buyers had come from is a bit of a conundrum.

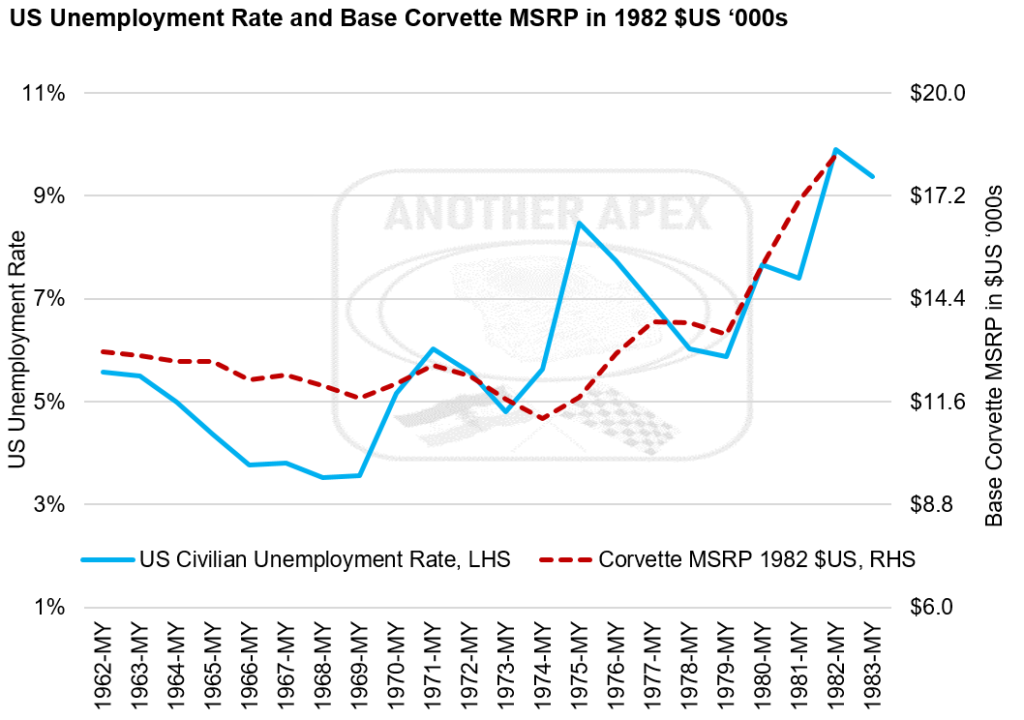

What made the increased demand especially surprising were the two increasingly severe recessions the US economy encountered between 1968 and 1978. And unfortunately, this economic trend would continue into the early 80s.

While the Corvette reached new sales records and continued to pack on features, a national energy crisis began to unfold. Middle East oil production had fallen dramatically after President Nixon’s 1973 promise to provide Israel with billions of dollars in emergency aid.[3] What crude did arrive in US ports was increasingly refined into unleaded and therefore lower octane fuel. Fuel that wouldn’t gum up the catalytic converters that were starting to appear. To accommodate the lower octane, engine compression ratios dropped along with horsepower and torque.[4] [5]

Hit from all directions – fuel economy, noise, safety, and emissions – the last banderillas found its mark in 1974. As the bull market collapsed, engineers began to see the big-block engine’s emission challenge differently; even with two catalytic converters it was not routine to comply with the EPA’s 1975 emission targets.[6] And it would have been hard to imagine sustained demand for such a thirsty engine in the economic environment of 1974.

With GM development resources frantically focused on newer V6 engines,[7] the Stingray’s 7.4 liter bruiser fell from the list of priorities. Thus, Corvette’s exalted big-block was granted an ‘indulto.’ It was spared extinction. And barring limited use in sedans in ’75 and ’76, it would only again appear in pastures under the hoods of new trucks.

A 1975 base Corvette having a 165 net horsepower 350 cubic inch small-block V8. Over 90% of ’75 Corvettes were equipped with this base L48 engine that was less potent than any C2 or C3 that preceded it. Note its painted plastic bumper, luggage rack, and luxurious wood-grained interior; both introduced in the mid-70s. Photo courtesy of Barrett-Jackson Auction Company

Fuel for the Economy

The US unemployment rate exceeded 5% in January of 1974 and within a year it would stretch beyond 8%. In a desperate measure, the US introduced a 55 mph national speed limit to save spirits. And some spirits were saved, but not initially those that had originally been targeted. The slower speeds helped reduce fatal collisions per mile in 1974, [see last chart in our part 5] but light vehicle’s fuel economy continued to erode.

The dire economic situation led to 1975’s Energy Policy and Conservation Act which proscribed CAFE fleet targets for automakers. The first turnpike was slated for the 1978 model-year, when Congress required 18 miles per gallon Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE). In the meantime, the oil shortage would worsen before it would improve.

Eventually, oil prices would quadruple, Nixon would resign, unemployment would double, and inflation would touch 10%. Over the next decade, it’s uncanny how America’s unemployment rate rose while base Corvettes managed to add pricing well beyond inflation [“real” pricing, see chart below]. Obviously, a Corvette is much more than utilitarian transportation. But because of its success raising demand and price during the atrophy of the 70s, it’s not hard to imagine that status had increasingly become a driver of demand for new Corvettes.

The Corvette’s Demand Plasticity

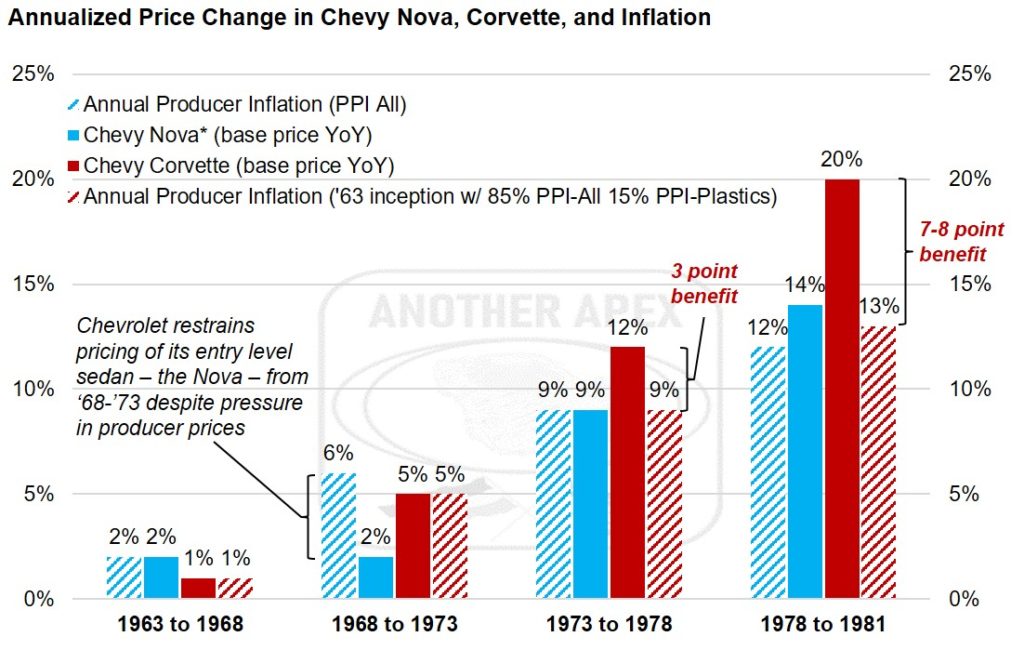

It simply amazing that the pricing of entry level cars – like the Chevrolet Nova (blue in chart below) – paced with inflation more or less (striped blue in chart below). But base Vettes racked up record sales while adding 3 percentage points of pricing beyond inflation from ’73-’78 (red in chart below). Based on strong demand, Chevrolet must have sensed a lot of headroom in MSRP still. Because after 1978, Corvette marketers escalated prices at a phenomenal 7-8 points above inflation annually over next three years (see chart).

Due to its fiberglass body, certainly Corvette’s raw material costs may have been more linked to petroleum. But in a steady state, raw materials typically only represent 10-20% of manufacturing costs. And even for a Corvette much of that is metal.[8]

Note: The rate shown is the compound annual rate of price change. ‘*’Includes Chevy II from 1963-1968 and Camaro from 1980-1981, for simplicity model-years assumed to start in July, and inflation data PPI also measured on July 1st. Chevrolet reduced the ratio of resin to fiberglass with the introduction of SMC in 1973, just before petroleum products prices soared. [18]

Source: Corvette Museum Archives, GM, Federal Reserve, Nova SS: Nova and Chevy II 1962-1979, Steve Statham, Motorbooks, 1997 The Complete Book of Chevrolet Camaro, David Newhardt, Quarto 2017,The Complete Book of Corvette, Mike Mueller, Motorbooks 2006, and Another Apex estimates 8/29/2019

To evaluate the potential impact of rising plastic on the Vette, the pricing comparison in the chart includes a composite measure of inflation in red stripes. It compounds from an initial 15% estimate in value contribution from plastic in 1962, and rises all the way to a 45% weighting in 1981. In fact, this composite measure of pricing ties well with the acceleration in the two-seater’s MSRP from ’63 to ’73. However, Chevy’s space capsule left commodity’s orbit entirely from ’73 to ’81.

Merry Men

Allowing the top shelf to gallantly lead GM’s portfolio – like Robin Hood on a mission to balance inflation pricing – was not as simple as intercepting and tolling commuting doctors and lawyers. Actually with their new CB radios, they had become especially elusive. No, in fact it wasn’t all professionals paying prices that seemingly violated fundamentals. Patriotic blue-collar enthusiasts from sergeants to steelworkers arranged loans – sometimes with annual interest rates nearing 20% [11] – to harness the inflating Chevy icon.

Despite the incredible rise in Corvette’s price, the St. Louis plant’s 1450 employees were working flat out during the 1979 model year and GM lacked footprint to expand or modernize their facility.[9] Continued demand could only be met through the construction of a new plant, which was announced in March of 1979.[10] Assuming high demand and high pricing continued, the new plant in bourbon country was a no-brainer.

Partnered with piquing prices, Corvette enjoyed continued publicity and panache even as its performance suffered. No example of this is more vivid than the 75-110% mark-up[11] (mark-up above MSRP) that dealers commonly received for the “Limited Edition” 1978 Indy 500 pace-car replicas.

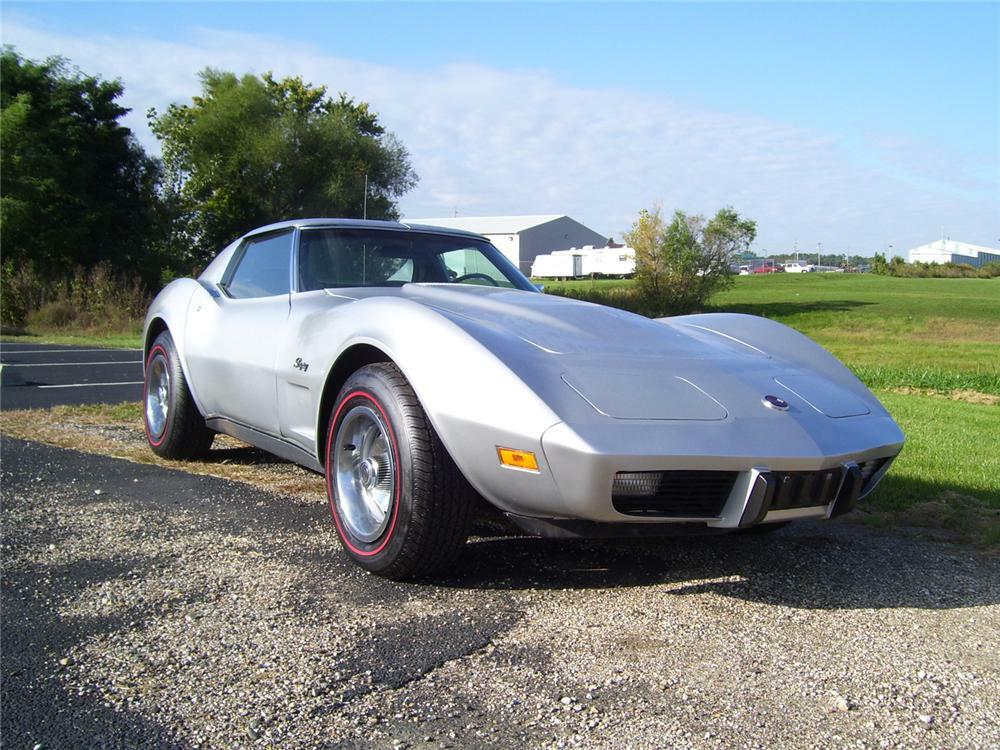

Cloaked in black and looking especially smart – with a silver air dam as sharp as one of Sir David Frost’s two tone Nixon interview collars – it commemorated Corvette’s 25th anniversary. Ostensibly spurred by a front page Wall Street Journal article that offered speculator’s assessments on perceived shortages and collectability, demand was so great that Chevrolet produced 6502 pace-car replicas, instead of 200.[12] The success of this approach may have given GM executives what seemed like an endless supply of celebrity capital from which to borrow.

Indeed, for casual car enthusiasts – such as those who rely solely on the Journal’s daily “Main Street anecdote” for advice on conspicuous consumption – additional pricing may have signaled fitness in product. If the 70s price increases conveyed capability, it might suggest some “plasticity in demand” for the late C3s.[13] In other words, some demand may have been symbolic instead of secular.

1978 Chevrolet Corvette Indy-500 Pace Car Replica with L82 350 small-block. The 220 horsepower L82 was a $525 option while the UP6 AM/FM Stereo with CB was a $638 option; both shown in pics. About 3000 of the 6500 ’78 pace-cars had the stronger L82; initially Chevrolet planned to build only 200 but there was high demand. Note the cut pile carpet that lines the transmission tunnel. Pictures courtesy of Corvette Mike Midwest, in Burr Ridge, IL https://corvettemikemidwest.com/used-corvettes-for-sale/1978-corvette-pace-car/

Eight-track Options

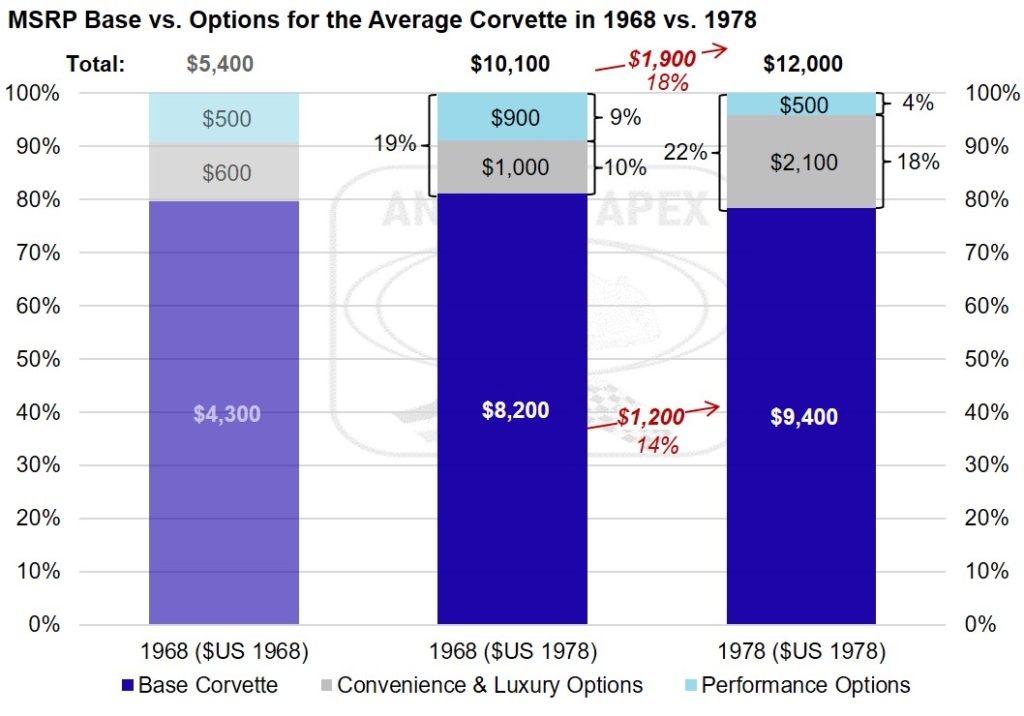

Clearly the Corvette marque’s success had accelerated well beyond its intent as a halo car with available performance parts. Parts that Chevrolet could make available to race teams and might trickle down to hot rodders. In fact, “heavy duty” and performance oriented options, as far as a percentage of Corvette sales, dropped from almost 10% in 1968 to less than 5% in 1978 (see the light-blue in the chart below).

At the same time that the racer’s menu of options – like the ‘L88 engines’ and the M22 “rock-crusher” transmissions – disappeared, luxury and convenience items, from luggage racks to extra speakers, doubled in average content. The chart below shows the average ’68 Vette had $1000 in high margin convenience and luxury options while 1978 buyers indulged in $2100 of such options. And these figures have been adjusted for inflation.

Although luxury and convenience options typically were more profitable for GM, the opposite was true of the high-performance components intended for the independent race teams and usually of limited production. Indeed if all the R&D costs for the aluminum big-block were considered, the ‘few hundred ZL1 engines’ produced in the 60s and 70s were certainly sold at a loss.[14]

In combination with iconic pricing power, the new luxury and convenience options helped spur an 18% jump in prices (29% with mix) over the 10 years ending in 1978.

Note: For simplicity model-years assumed to start in July, and inflation data (Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers) also measured in July

Source: Corvette Museum Archives, GM, Federal Reserve, and Another Apex estimates 8/29/2019

From Corvette to Cash Cow

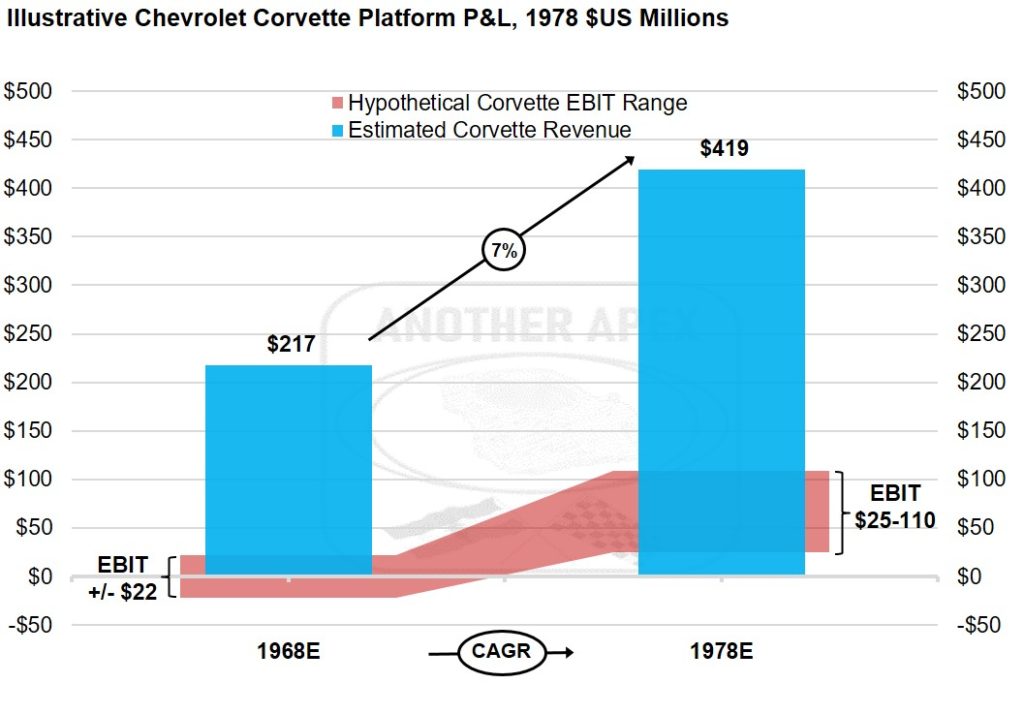

Just the increased real pricing [inflation removed from 1968 to 1978] might [15] have boosted GM’s bottom-line by $25 million. And the additional pricing on the 64% increase in quantity was likely good for another $17 million. As a result, the aggregate pricing bounty may have been good for more than $40 million. For perspective, GM was making approximately $3000 -4000 million annually during this time.

In today’s dollars, $40 million would translate to over $150 million. And by Detroit standards that’s a huge contribution from a decade of pricing work on the same basic low-production model. Let alone one whose original mission wasn’t as much profit as it was publicity and helping legitimize a racing parts bin.

The exercise below uses suggested pricing – over and above inflation – in conjunction with known sales volumes to consider how significant GM’s Corvette profit was in 1978. The hypothetical operating contribution is illustrated in red and implies that the Corvette platform likely hit double digit margins in the late 70s.

Note: EBIT designates operating profit [before interest and tax); all $US are adjusted to 1978 $US using 2Q closing CPI as a proxy for model-year; revenue assumes GM receives 75% of MSRP and dealers absorb any variance from MSRP; CAGR indicates compound annual growth rate.

Source: Corvette Museum Archives, GM, Federal Reserve, and AnotherApex estimates 8/29/2019

In fact based on a doubling in revenue from ’68 to ‘78 – see blue in chart above – it’s very likely that the old C3 set aside its halo, unbuttoned, and began moonlighting as a cash cow. Such enterprises may have well more than doubled Corvette’s profit contributions.

Consider that in 1978 GM was the largest company in the world, and only 1 of every 200 vehicles it sold worldwide was a Corvette.[16] Yet so potent was the Corvette’s popularity and pricing power in the late 70s, that $2-4 of every $200 in GM profit might have come from the brand leader.

No doubt, Chevrolet dealers and GM executives had become fans of ‘The Cars,’ and were whistling along with “Good Times Roll” in 1978.[17]

Written by Jez Stephens

[1] 1968’s 235 net horse power 327 engine at 75% power equates to 176.25 hp, roughly the same as the 1977 L48’s published 180 net horsepower.

[2] 14% real increase in base price over the decade ’68 to ’78 when adjusted for CPI and 18% increase in “as equipped” MSRP over the same period.

[3] https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/oil_shock_of_1973_74 referenced 8/8/2019

[4] Fuel Additives: Uses and Benefits, ATC https://www.atc-europe.org/public/Doc113%202013-10-01.pdf accessed 2-1-2019

[5] John Bachmann et al http://www.epaalumni.org/hcp/air.pdf accessed 2-1-2019

[6] Corvette, America’s Star-Spangled Sports Car, Karl Ludvigsen, Automobile Quarterly, 1977, page 242

[7] Chevrolet Engineer Gib Hostader comments of 1973/1974 “The purge was on V-8s. Everything was going to be V-6.” noted by Jerry Burton in his book Zora Arkus-Dontov published by Bentley 2002, page 356

[8] https://www.autonews.com/article/20181013/OEM10/181019800/material-prices-hammer-the-industry and https://legacy.alixpartners.com/en/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=738b8Eseczg%3D&tabid=635 accessed 8/20/2019

[9] Legendary Corvettes, ‘Vettes Made Famous on Track and Screen, Randy Leffingwell, Motorbooks, 2010, page 138

[10] Jim Smart http://www.superchevy.com/features/1907-corvette-assembly-plant-bowling-green accessed 8/20/2019

[11] Tom Russo and Jay Heath, Corvette Magazine, October, 2018 http://www.hunt4cleanair.net/Articles/IndyVette.pdf accessed 8/29/2019

[12] WSJ 3/27/1978 “Few Want to Drive This Car, but Many Are Eager to Buy It, Collectors, Speculators Bid Up Process of ‘Indy Corvettes’ Before They Reach Market,” Tom Russo and Jay Heath, Corvette Magazine, October, 2018 http://www.hunt4cleanair.net/Articles/IndyVette.pdf accessed 8/29/2019

[13] When introducing the concept of the “plasticity of demand,” the book Behavioral Economics and Brand Choice emphasizes the “The social status and esteem that [a Mercedes, etc.] driver is accorded are the symbolic rewards of consumption [i.e. not utilitarian rewards].” Indeed, utilitarian item’s demand “elasticity” can be stretched – resulting in price swings that follow demand. On the other hand, brands that are valued based on social significance – such as 70s Corvettes – might offer demand ”plasticity.” Demand dependent on symbolism that can be molded like fiberglass. Due to its flagging performance credentials, this period of Corvettes likely combined an element of utilitarian and symbolic consumption.

[14] However, some or all of Chevrolet’s R&D in alloy engine blocks and components were likely charged to Chevrolet or GM as a whole due to the benefit on all models. For example, the Vega’s four cylinder engine block later used alloy similar to the Can-Am/ZL1 engines.

[15] “might” indicates the following hypothetical exercise that attempts to determine the annual run-rate EBIT and EPS benefit (in the 1978 model year) from price increases BEYOND inflation (CPI) from the 1968-MY through to the 1978-MY):

- 1968 MRSP in 1978-MY dollars is (66.1/35.1)*($4300+1100)=$10,100 for 1978. But 1978-MY actual MSRP was $12,000 an increase of $1900 in real pricing and mix (urban consumer CPI used). 1968-MY production of 28,566*$1900 is $54.3 million in 1978 dollars; $54.3_million*75% to GM (25% to dealer) = $40.7 million in 1978-MY dollars.

- But that’s only 1968-MY production levels, 18,210 additional Corvettes were sold in 1978-MY. At $1900 in real pricing each that equates to $34.6 million in 1978-MY dollars. $34.6_million*75% to GM (25% to dealer) = $25.9 million in 1978-MY dollars. Thus, the total potential contribution of real pricing on incremental margin benefit since 1968 – represented only during 1978-MY – was $66.7 million in 1978-MY dollars.

- With tax of 35% and 286.9 million shares that suggests $43.3 million in NI and EPS impact of $0.15 in 1978-MY. For reference CY1978 EPS was $12.24 and CY1977 was $11.62.

- $66.7 million in EBIT in 1978-MY would have been good for 16% EBIT margin on Corvette’s estimated $416 million in ’78 model year sales ($420 million ~= 46.8K Corvettes sold at $9400 base price/Vette + $2600 in options/Vette, less 25% of MSRP staying at dealers or being saved by discounts). Including the real pricing benefit if total Corvette Platform EBIT was 21% or 27% for 1978-MY [if margin expanded 5– 11 percentage points from ’68 to ‘78] the resulting EPS impact after 35% taxes calculated as above would be $0.20-$0.25 contribution to 2H77 and 1H78 EPS of approximately $12.00.

- EBIT and EPS estimates include overhead. This assumes production equals sales volume, no operational leverage, dealers absorb any variance from MSRP, and no changes in cost structure.

- Base Figures from Original Corvette; the Restorer’s Guide 1968-1982, by Tom Falconer, MBI publishing company, 2001 and GM Filings.

[16]Worldwide GM sales were 9,068,000 in 1977, so 1 of 200 is approximated for simple illustration. https://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune500_archive/full/1978/ accessed 8/20/2019

[17] https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-lists/500-greatest-albums-of-all-time-156826/barry-white-cant-get-enough-173683/ accessed 8/29/2019

[18] Barry Kluczyk, https://media.gm.com/media/us/en/gm/news.detail.print.html/content/Pages/news/us/en/2012/Aug/0816_corvette.html accessed 8/20/2019